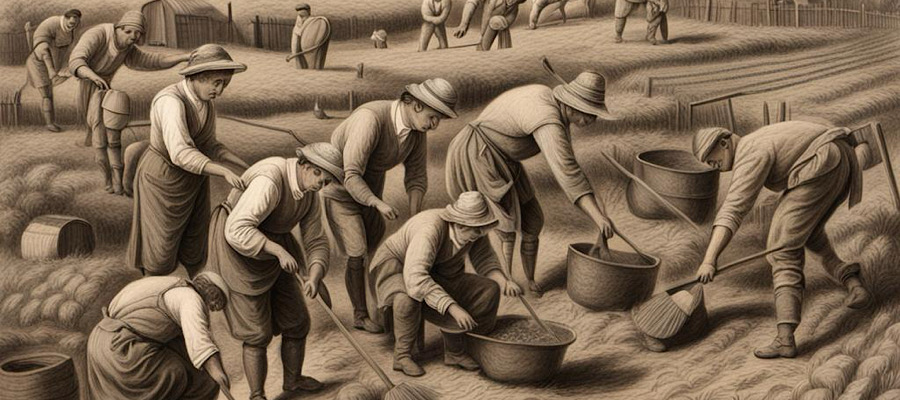

Open fields and common land were appropriated, creating Legal Property Rights for a handful of people, denying access and use to the rural poor and driving them from the land. 6.8 million acres were enclosed. Creating a land-owning oligarchy that effectively dominated political and domestic life in Britain until the Representation of the People Act, better known as The Great Reform Act of 1832. Which of course changed very little, merely sweeping things to one side in the usual English fashion.

There is no doubt, of course, that these huge changes to the realm altered forever the individual’s relationship with the land. It also enabled what we now term as the Agricultural Revolution

Numerous factors accounted for these changes.

From 1348 - 1665. From the Black Death to the Great Plague of London, disease had managed to keep the population down.

The Black Death was the most successful at this, culling at least 50% of the population in Europe and between 70 and 200 million souls worldwide. Humans being humans didn’t let this set them back too much and as the disease retreated over the 300 odd years they soon began to increase their numbers once more as life for the survivors took on a different aspect. By the 1600’s this had begun to upset the ruling elites who were still entrenched in their pre -pandemic mindsets.

Think of the Divine right of Kings and the subsequent attempts by the People to limit their royal prerogatives. Oliver Cromwell and his English Revolution springs to mind. For a while the idea of Common Wealth was certainly a thing. Although the Puritans and their sects were excessively dour, repressive and just a tad violent, their hearts were somewhat aligned with concept of for the good of all. The ownership of everything by the people for the people and administered by their elected representatives rather than an autocrat that believed that he and he alone had a hotline to God.

Needless to say as soon as the English had ushered in the Modern World, they chickened out and invited Charles 2 back in 1660 with restoration of the Monarchy. Charles was already King of Scotland having been voted in by the Scottish Parliament after his Father’s Execution in 1649 at the height of the Revolution so it kind of made sense to have the same family in charge, even if he could only speak French - not true of course, he was a famous Polyglot. By his own admission he spoke Spanish to God, Italian to women, French to men and German to his horse.

It could be argued of course that the elites led by this alleged French popinjay decided to exact their revenge on the upstart people by driving them off the land. Land after all is power. Enclosing the land as a strategy for controlling the populace had been sporadically used by the controlling classes since the 12th century, just without the backing of the Law. Now that they had the backing of the King and the legal means to force their policies through, thanks to the Parliamentary reforms of the Cromwellian Age, they went hell for leather and stepped up their expropriation - enter the Age of the Oligarchs. Big fancy houses, landscaped, well, landscapes euphemistically called gardens. Lots of painters to validate their actions, fancy clothes, balls, investment in overseas estates etc etc. at least that’s how some social historians view this period.

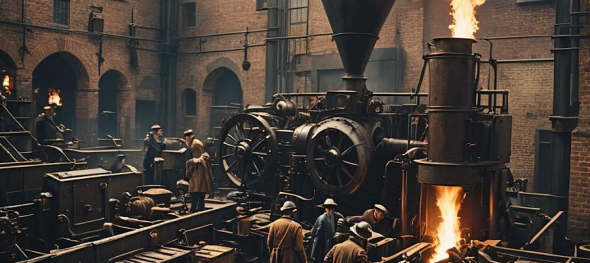

Where did all the money for these fancies come from? With all that land on hand they began to look for ways to exploit it. First agriculturally and then industrially with a hefty dose of what used to be called Vikingr or Piracy to you and me. Overseas trade increased rapidly bolstered by the new types of instruments that had been devised, originating in the maritime heritage of the Danelaw, centuries before. The concepts of Companies Limited by Guarantee and Monopolies matured under the Mediaeval theories of Royal Charter. The most famous of which operated something like a private, marauding mercenary Pirate ship - the East India Company, sometimes referred to as John Company. Expansion into the New World and all that fun. It was certainly a Century of rapid change and expansion. By 1750 GDP was growing at 1% per annum. Not much you say, but it came to define the moment of change from stagnation to revolution. From Agricultural to Industrial. By the time of the 1851 census more people lived in the towns and cities, engaged in industry than lived in the countryside and drawing their sustenance from it.

There was also a hungry population that had been rising steadily from around 3 million in 1550 to 4.4 million in 1570 and thereafter exponentially to just over 9 million by 1801. It then doubled and doubled again and continued to grow in spite of major wars and pandemics. It probably stands at around 90million today. It couldn’t feed itself then and certainly can’t today. Thus the idea that Britain might like to at least try is as outmoded and unfashionable as it ever was. Nearly as comedic as the concept that we might like to try to make things once more.

Landowners looked into improving their assets and with millions of folk who needed to work for peanuts the whole system was ripe for exploitation, corruption and abuse. So began what we like to call the Industrial Revolution.

It would take few years, but along would come Marx and Engels to tell the world how England had been doing it all wrong, by which time everything had changed once more. Always late to the party those two.

.